In the medieval era, it was widely believed that a malady or illness could be transferred from one person to another or to an inanimate object on the strength of prayers and donations.

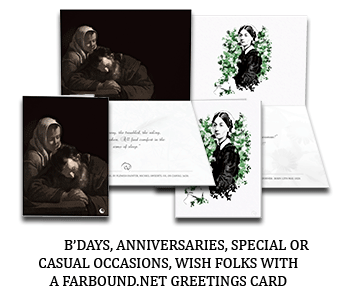

One powerful piece of evidence that proves this rite actually existed lies in the heart-touching story of the Gurkhani emperor Babur and his beloved son Humayun – a pair of father and son regents who lived and died in the 15th century.

The Humayun-Namah, penned by Humayun’s Half-Sister Gulbadan Begum, reveal how this episode unfolded. Writes Gulbadan, upon his unrequested return from Badakshan (now in present-day Afghanistan), Humayun took up residence in Sambhal (a region now in the present-day state of Uttar Pradesh in India) that was gifted to him as his fief.

There, however, and within six months of his stay in the hot and humid weather, Humayun, was taken gravely ill with a mysterious fever, which had refused to subside in spite of the court physicians’ best efforts.

At their wits’ end and with no other alternate course available, the court physicians had ultimately appealed to a deeply distressed Babur to participate in the rite of transfer of illness.

This rite was a popular rite in medieval times and was undertaken in extreme cases when all possible human means had failed to find a cure for a serious illness. At the heart of this rite was a medieval and superstitious belief that an illness could be transferred with heaven’s intervention.

Although the Hakim’s (Court Physician / Doctor) suggested choice is widely known to have been the Kohinoor diamond, which was gifted to Humayun by the family of the king of Gwalior, Bikaramjit, in gratitude for sparing their lives. The dervish Babur had staked his own life in exchange.

Babur had considered the now world-famous diamond to be unequal to his son’s life, and himself as the cherished object of his son’s affections.

Remembers the Humayun-Nama, in extreme hot weather and with his own internal organs burning from a prolonged illness, a weakened and inflamed Babur had circled the bed of his dying son, Humayun, three times.

Praying out loud, “If a life can be exchanged for a life, I, who am Babur, give my own life and being in exchange for my son”.

While the prince’s health is recorded to have gradually improved while Babur’s had deteriorated for the worse, leading to his death on the 26th of December in 1530 CE, the miracle that was the transfer of illness has been undermined by historians on medical grounds as the real cause of his death.

Says historians, Babur had been ailing for a long while from discomfort of the intestines, which, according to the court physicians of the period, was due to the poison administered to him by the mother of his rival Ibrahim Lodi, the Afghan king whom Babur had vanquished at the battle of Panipat. Humayun’s illness, on the other hand, was high fever.

The poignant real-life episode, however, has come down the ages as a profound testament of a father’s love for his children, and the distance a distressed parent can go for the well-being of an offspring.

Babur, a Sunni muslim, had prayed to Hazrat Ali, a prophet of Islam a Sunni Muslim generally does not pick, and even in his weakened condition, fasted for many days for his prayer to be answered.

‘Hazrat Ali’, sometimes simply known as ‘Ali’, was the son-in-law of Muhammad, the founder of the religion of Islam. He was one of the four early Khalifas (successors of Muhammad) and the first Imam of the Shia sect of Muslims.

While in the medieval times, Shias and Sunnis were bitter enemies. In present times, Hazrat Ali, is revered and held in high esteem by both sects.

I F I This is an independent story on the medieval rite of the transfer of illness. It has been created out of literary sources, especially the Humayun-Namah by Gulbadan Begum and Humayun Badshah by S.K. Banerji I