Humayun’s Mausoleum Complex, Nizamuddin East, New Delhi, India.

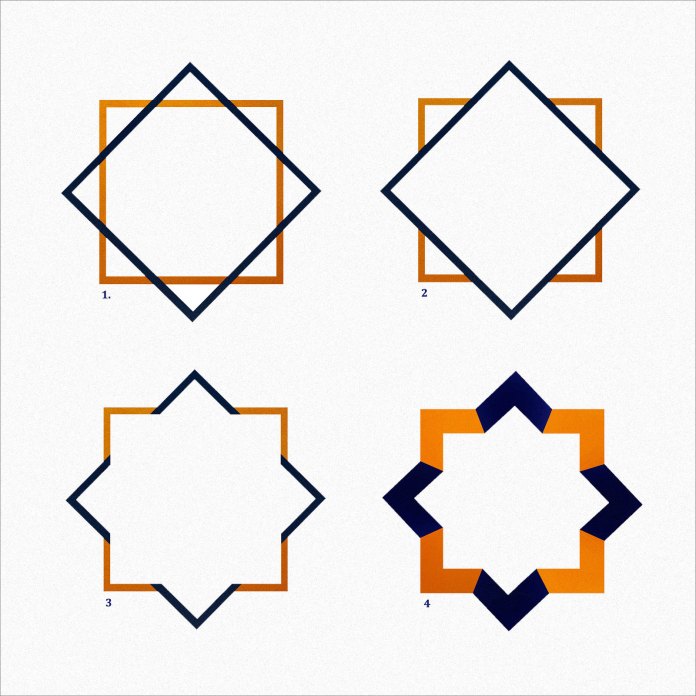

Arabic symbols: Eight-pointed star of Jerusalem.

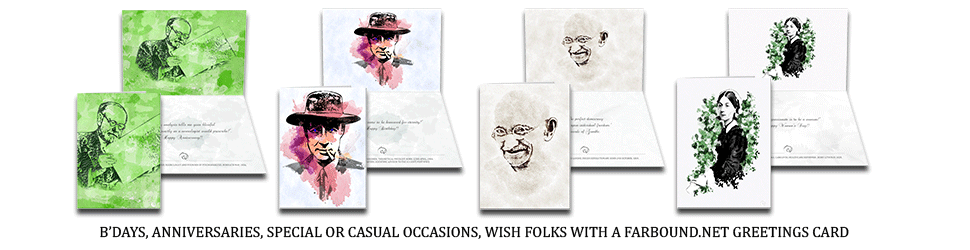

Embellished on the foot of a red stand stone pillar holding the massive plinth of Humayun’s mausoleum on top, the Najmat -al-Quds or the eight-pointed star of Jerusalem bear silent testament to the enormous contribution Arabic art has made in propagating the faith of Islam relying solely on decorative motifs, beautiful calligraphy and geometric symbols that merged aesthetics and spirituality to endow majestic buildings with beauty and grace without deviating from the Quran’s restriction on portraying human imagery.

An auspicious element extensively used in medieval Islamic architecture in Moor dominated southern Spain and the Middle East, the Najmat-Al-Quds possibly made its first appearance in Hindustan during the reign of the third Gurkani emperor Jala-ud-din Muhammad Akbar – a period that had witnessed the construction of the mammoth UNESCO world heritage site by the experienced hands of Arabian artisans and the Persian architect, Mirak Mirza Ghiyas.

Specifically imported in from their distant homes by Humayun’s chief consort and queen, Bega Begum, to honour her deceased husband’s fascination for Persian art, architecture and culture, that he had picked up during his fifteen years of exile – and which at a point in time taken him to the realm of Shah Tahmasp, in what is today the country of Iran. (see Farbound.Net snippet: 15 years of Humayun’s exile on a Google map).

Produced in white on the surface of the mausoleum, a colour that in Arabic culture is known as the ‘Abiath‘ and largely associated with nature, purity, peace and contradictory a white coffin in this case accidentally or intentionally, a befitting choice for the final resting place of Humayun, a much harried Sunni regent who spent most of his reign troubled by fateful events, the eight-pointed Najmat-al-Quds’ significance in Islamic art goes beyond mere decoration, as the symbol’s incorporation in possibly the 7th century, some eight hundred years before Humayun’s time, commemorated a new landmark in the growth of Islam.

A religion that had blossomed in Mecca, an ancient oasis in western Arabia, forty years after the birth of its founder, the prophet Muhammad, in 570 A.D. Then uniting the warring tribes of the region had expanded rapidly across the east under the leadership of the Rashidun and Umayyad caliphates – and which later, in the 15th century, spearheaded by the Turks, Turcko-Mongols, Ottomans and Moors had sprawled from Hindustan to Turkey in the east and Spain in the west. With Arabic art, architecture and writing upholding the awning of its phenomenal growth as a colonnade of faithful pillars.

Evident in the creation of the first Quran that came written in an Eastern Arabic script, the importance Islamic states placed on the mandatory learning of the Arabian language, even well past the medieval age, and the hiring of Arabian talent for building colossal architectural projects decorated with intricate carvings and bejewelled interiors.

Which spoke highly of the refined skills vested in the Arabs, but with the passage of time eclipsed the role of the Christian Byzantine architects who at the nascent stage had schooled the Arabs in the nuances of architecture, during the construction of the Dome of the Rock shrine in the city of Jerusalem in 691 A.D.

A monumental building that had not only inspired the Arabs to master and perfect the techniques of transcendental architecture and decorative arts to surpass those of other religions but was also the symbol of their first Qibla, Jerusalem. A building that was artistically represented with the geometrical Najmat-al-Quds, an eight-pointed star with a long history, but which the Arabs adopted and modified to decorate places, tombs, courtyards and carve on coins, to serve as an auspicious reminder.

The origin of the eight-pointed star.

Like the six-pointed Najmat Dawud, the hexagram, that appeared in ancient cultures across the world with vastly different interpretations and was used in medieval Hindustan as an architectural element by both the rulers of the Delhi Sultanate and the later Gurkanis in a genre known as Indo-Islamic architecture (see Farbound.Net snippet: The star of David or the Hindu Shanmukha), the eight-pointed star has also been observed to have existed in various renditions with civilizations and cultures.

That cropped up at different stages of world history to develop the geometric symbol in perfect isolation or inherit it as rightful heirs of distant ancestors and in turn, bequeath it to the generations that followed – to transport it from one part of the earth to another via mass migration, independent folk movement or trade of commodities.

Notably in the historic civilization of Sumer in ancient Mesopotamia where archaeological work excavated the earliest known form of the star dating back to 4,000 B.C., and which depicted the symbol as a starburst associated with the Sumerian goddess of love, desire, fertility and war, Inanna (Ishtar) – a deity who later is believed to have inspired the Greek Aphrodite and her Roman equivalent, Venus.

The Islamic Najmat-al-Quds and its predecessor the Rub-el-Hizb, however, are two unique variations of the eight-pointed star that inherits at its core a set of overlapping squares and a symbol that can be more strongly and clearly traced to similar Roman-Byzantine designs that existed in the east, especially during Christianity’s early phase. Attested by findings in Akhmim, upper Egypt, by archaeologist Albert Kendrick in 1920, which revealed their existence in Christian graves, dating back to between the 2nd and 4th century A.D. – approximately two hundred years before the advent of Islam.

The incorporation and subsequent modification of the square-based star by Islam as per its own philosophical framework was a natural process of acculturation and a pattern in history well observed with earlier civilizations, particularly the anteceding Romans – who in their time had assimilated symbols, weapons, and practices of subjugated cultures, especially of the Greeks, before transmitting them throughout the length and breadth of their vast empire that at its height had encompassed nearly 5 million square kilometres stretching from England to Armenia in the east and from Spain to the tip of the Persian Gulf in western Asia – making it one of the largest empires of antiquity that at its heart upheld Roman traditions and values yet remained till its very end a multiracial and cultural entity.

Events that preceded the Najmat-al-Quds.

Islam’s adoption of the eight-pointed star occurs in a period which it would seem had been pre-destined to witness major changes in the political and religious fabric of the east, and a recurring drama in the human timeline that since the establishment of the first human settlement revealed itself in a chain of episodes highlighting the rise and decline of civilizations – and a story-line that almost always revolved around the sprouting of gifted kingdoms, their growth into empires, and ultimately their replacement by other emerging powers. A cycle that had continuously turned with the wheels of time, sometimes frequently and sometimes with vastly paced interludes in-between.

Similarly, Islam’s founding and the Arabs’ subsequent appearance on the world stage just so happened, that without any elaborate planning on the part of the Arabs, it perfectly coincided with the critical phase of the two superpowers that had dominated and battled each other in the east for centuries: The Sassanid Persians and the Roman-Byzantines (once the eastern branch of the expansive Roman empire). And the timing couldn’t have been more perfect, for at this juncture of history, exhausted and weakened by decades of warfare that had frequently enveloped them from all sides, both the Persians and the Byzantines had been utterly denuded in resources, energy and had desperately needed time to recuperate and regain back their strength.

The conquests had originated in 633 A.D., roughly a year after a civil war had erupted amongst Muhammad’s disciples following his death in 632 A.D., and brought to the fore the Rashidun Caliphate, a group of elites related to the prophet himself through nuptial ties and whose debut in the theater of war, had witnessed the rapid subjugation of Sassanian territories in Mesopotamia (modern-day Iraq) in a short but vicious four-month military campaign. Followed by a full scale invasion of the territories held by the Sassanian’s long time foes, the Byzantines, in the region of Roman Syria.

Though the actual cause that led to the invasion is debated with some Arab sources stating the conflict with the Byzantines erupted over the murder of an Arab emissary by their allies, the outcome nonetheless had been overwhelmingly in their favour. Beginning with the battle of Ajnadayn fought in 634 A.D., the battle of Fahl in 635 A.D., the battle of Yarmouk in 636 A.D., Arab military prowess was to deal the more experienced Byzantine army a successive string of defeats, then with the same speed and aggression annex the cities of Jerusalem, Gaza and Antioch in 637 A.D., followed by Roman Mesopotamia in 638 A.D., and Babylon and Egypt in 640 A.D.

The successive chain of victories ultimately proving instrumental in establishing the Arabs as a recognizable power in the east and the masters of practically the entire region that stretched from Egypt to Mesopotamia, harbouring within its borders a large talent pool of architects and artisans well versed in the Sassanid and Byzantine school of design.

More unexpectedly, what had followed in the aftermath of the Muslim Arab’s dominance in the east was not the sullen animosity of a subjugated people or unrest and armed resistance, for the very reason the Muslim Arab at the time was not seen as a conqueror but a liberator who by effectively bringing to an end the Byzantine regime had freed the east from oppression, particularly in the city of Jerusalem where the religious community and hardliners had harboured a deep grudge towards the Romans since their occupation in 1 B.C.

Jerusalem’s relation with the Romans for most its history had been a violent and bloody one, which over the centuries had led to three failed rebellions, and at one point of time, the destruction of the second Jewish temple on the top of a low hill revered by Judaism as Har HaBayit – a 420-year-old temple that had been immensely sacred with its roots tied to the Biblical Solomon, which even Herod, one of Israel’s greatest historical king and an energetic builder had enlarged and beautified during his reign, while delicately balancing the sentiments of his subjects with the alliance of Rome, to prosper his kingdom of Judea.

The second crucial element that had made the takeover smooth and reduced cultural friction had been a high degree of tolerance exhibited by the early Arab caliphates, which had allowed both Christianity and Judaism to co-exist alongside their own religion of Islam – a faith which itself had shared many similarities with the older monotheistic orders and recognized its legendary kings and prophets Abraham, Moses and the messiah Christ as the chosen messengers of God, with Muhammad himself claiming to be a prophet hailing down their line.

Two vital factors that had eventually facilitated the unchallenged building of a Rashidun era mosque on the same holy hill the Arabs would henceforth call Al-Ḥaram al-Sarif or the noble sanctuary, and later Islam’s first major architectural project, the Dome of the Rock shrine which encircled at the centre the very rock Judaism and Christianity revered as the Holy of Holies, while the Muslim Arab, held sacred as the spot the prophet Muhammad had ascended to heaven, accomplishing in the course of a single night the Isra and Mi’raj, as described in the holy Quran and specifically by the name of Jerusalem in their sacred canonical scriptures, the Hadith.

The majestic architecture of the shrine and the subsequent development of the Najmat-al-Quds, however, was to come from an eastern landscape dotted with Byzantine architecture and symbols of the dominant faith of Christianity – whose elegance and decadence was to inspire and spur the Muslim Arab to also celebrate his own religion with a monumental building that could stand at par with Christianity. And one he achieved in the most symbolic way possible by having it build over the Roman’s pagan temple of Jupiter. Which in turn had been built over the remains of the second Jewish temple, destroyed by the Romans in 73 A.D.

The first appearance of the eight-pointed star in Islam.

Commissioned during the reign of the Arab Caliph, Abd-al-Malik and his son Al Walid I of the Umayyad dynasty, in 687 A.D., the gigantic structure, completed in 691 A.D., was Islam’s first foray in resplendent architecture and the school that endowed Arabian architects and artists with important lessons in architectural construction.

If from the Sassanid Persians the Arabs picked up the love for infusing buildings with lofty arches, ornamentation and Persian style pleasure gardens that had existed in the east since the time of Darius and already inseminated Greek and Roman life in the past. From the Byzantines, they acquired the techniques of building colossal domes on tall drums that became a central element in later Islamic buildings around the world including the mausoleum of the Turcko-Mongol Humayun in Hindustan, and much later the Taj Mahal constructed by his great, great-grandson Shah Jahan in memory of his favourite wife Mumtaj Mahal – both of which bear a distinctive Arabian style dome with a gentle tapering tip set in the middle of a Persian Garden.

Modelled after early Roman-Byzantine structures, particularly Christian sanctuaries that embodied the octagonal floor plan in a perfect synthesis of the circle and the square. An architectural style that had sprouted in the west and evolved over the centuries by the Romans and the Greeks, the Dome of the Rock Shrine was a masterpiece created by Byzantine Christian artisans working inside Islam’s guidelines – and a joint venture that facilitated the transmission of technical construction methods, interior decoration, and embedded at the heart of the Muslim Arab, a passion for mathematics, particularly geometry – which he was to later champion in and take to greater heights.

Here inside the hallowed space bejeweled with exquisite works of marble, intricate glass mosaics, mother of pearl inlays and decorations of semi precious jewels that coursed smoothly along the shrine’s identical octagonal divisions complimented with ambulatories and Byzantine style marble lattice windows that looked up at a towering wooden dome covered with gilded metal placed over the sacred rock right in the center – for the first time in Islam’s history, Arabic motifs inspired by Hellenist designs and Arabic calligraphy in the form of Quranic verses made its appearance as did the eight pointed star both as a symbol ingrained into the interior decoration and in its architectural pattern.

What made the acculturation possible.

Christianity and the more ancient Judaism had never been two religions alien to the Arabs nor had the culture of the Sassanid Persians and the Byzantine Romans. For before the founding of Islam, though a largely polytheist culture that worshipped nature, demons, spirits and a black meteorite stone known as the Kaaba which resided in Muhammad’s home town of Mecca and made it a pilgrimage centre, the Arabs had been both Christianized and adherents of Judaism.

The gentle and intermittent form of precipitation had occurred in the most natural manner as the Arabs had lived in almost the same neighbourhood where the two religions had flourished with established trade links and political ties with not just the Christian missionary disembarking from a caravan passing through and the Jew merchant but also with both the Sassanids and Romans – empires that from time to time had befriended and enrolled their help, such as the Ghassanid Kingdom that acted as a buffer state for the Romans, safeguarding their borders against incursions from other Bedouin and Arabian tribes.

Likewise, when the actual process of acculturation begun, the Muslim Arab already immersed in the ideology and beliefs that prevailed in the east had been open to architectural styles and incorporating symbols that predated the founding of Islam. Even if they happened to be distantly related to the teachings of the Quran.

Their adoption of the Byzantine octagonal sanctuary design and decorative elements wasn’t just out of a profound sense of reverential respect, though it definitely did exist to a large degree, but a selective process that kept the components that came close to their own ideologies, altered what could be altered and completely do away with those that weren’t required, explaining the absence of the altar and choir in the shrine and in later Muslim religious buildings but the repeated use of the dome and the octagon as primary architectural elements whose relation in theology binds both the physical world and heaven in perfect symmetry.

Yet like in Europe, late roman architecture inspired the Gothic, Visigothic and Medieval styles, so was Islam a rightful heir of Byzantine construction skills in the east that formed the launching pad for its later architectural flight. One that was largely made possible for the many similarities Islam shared with Christianity and the purity it had found at the core of Byzantine Christian sanctuary architecture which like it, a monotheist religion, professed the concept of unity with the one true god.

And just like the Arabs acceptance of the octagonal architecture of the Roman-Byzantines that with slight modifications had matched with the Quran’s teachings – conspicuously felt in the structure of the central dome within the shrine and flows down to meet the eight corners of the octagon in the centre corresponding to the Quran’s description of eight angels upholding a divine throne. So had the eight-pointed star found a place in Islam, which in geometry is the next logical step in the transition of an octagon to the octagram.

The significance of 8 both the octagon of the shrine and octagram of the star inherited was deep rooted and in almost all cases resonated with spiritual undertones. In certain cultures like that of the ancient Egyptians, the number 8 corresponded to 8 primordial deities. In Judaism 8 indicated the number of people Noah saved in his ark at the time of the great flood, the duration of the festival of Hanukkah which commemorated the Israelite’s victory over tyranny and desecration of their temple, the day when circumcision was introduced at the time of their prophet Abraham and again the day a boy child was circumcised. In ancient Greece, the 8 rooted in mathematics was the symbol of geometric perfection. In Christianity 8 was associated with the resurrection of Christ and new beginnings. While in Islam 8 formed the number of gates of the Islamic Paradise, the eighth step on which Muhammad during his heavenly journey saw angels prostrated in reverence and the eight angels who upheld a heavenly throne.

Thus to the Muslim Arab, the ideological significance of the eight-pointed star was not only a match in terms of his own doctrines but when produced by combining two geometrical squares it perfectly happened to compliment the structure of the shrine from both the interior and exterior – as seen below in the backdrop of the Dome of the Shrine, with both the Najmat-al-Quds and its predecessor the Islamic Rub-el-Hizb, which inspired it.

The symbolic significance of Najmat-al-Quds.

The Islamic eight-pointed star that the Arabs were to call Najmat-Al-Quds was not an Arab creation but one like the architecture of the shrine existed within the broad canvas of Roman-Byzantine designs, especially with Christianity and Judaism, which continued its use even well after its incorporation and popularization by Islam in possibly the whereabouts of the 7th century – evident on the surface of the Leningrad Codex, the oldest Hebrew Bible internally dated to the 10th century A.D., which depicts the symbol on the cover encompassing a hexagram.

The Arabs’ achievement, however, was the significance they associated with the eight-pointed star by binding it specifically to the Dome of the Rock Shrine in Jerusalem and spreading its fame with decorative art through Islamized regions that by 750 A.D., had come to broadly encompass the Arabian Peninsula, the Caucasus, Levant, Mesopotamia, Persia, North Africa, Central Asia, Sindh, Afghanistan, Spain and France.

While the Rub-el-Hizb with a circle in the centre formed a distinctive connection with the Quran, becoming a symbol marking the end of its approximately equal length 60 divisions and a guide that facilitated the recitation of the holy book, the Najmat-Al-Quds was the geometric representation of the Dome of the Shrine in Jerusalem that was Islam’s second holiest place next to the Mecca and the religion’s first Qibla – not to mention an important milestone in the growth of Islam.

The legacy of the Arabs.

The golden age of the Arab caliphates was not destined to endure as long as that of their foes, the Byzantines. Underlying strains that existed among the ruling elite, particularly in the Shia and Sunni rivalry that well begins in Muhammad’s own birth land, unravelled most of the political accomplishments the Arabs had rapidly achieved in less than a span of 200 years, and like the Romans whose later dependency on foreign mercenaries affected the stability of their empire, so were the Arabs ultimately supplanted by the Turks in the proximity of the 11th century.

The forerunners who established the momentum with their brilliant victories, the Rashiduns, directly related to Muhammad’s line by nuptial ties, found themselves supplanted not long after their capture of the holy city of Jerusalem. The Umayyads who succeeded them and build the famous Dome of the Rock Shrine, eventually met the same fate at the hands of the Abbasids, though they managed to retain their hold in Spain for a very long time. The Abbasids in turn while instrumental in greatly expanding Arabic repute and turning Islam into a cosmopolitan religion also watched their sovereignty crumble with the emergence of the breakaway faction, the Fatimids in Egypt and later the Buwayhid dynasty in Persia. Hastened more by the Mongol Invasion in 1258 A.D. – factors, in the long run, undermined the Arabian dream of a politically united people, in spite of Islam’s potential adhesive power.

But the role the Arabs played in establishing Islam and ushering in a new chapter in world history remains an unrivalled and unequalled achievement among the cultures of its time. Emerging from the Arabian Peninsula, a 1,300km wide and 1,200 long inhospitable land, almost entirely covered by the shifting sands of the Arabian desert that occupied 900,000 square miles of its surface area and made the daily requirement of survival in that arid and scorching environment, a remarkable feat in itself – the Arabs had gone on to defeat the two most powerful empires in the world that existed during the period and progress an idea that without their participation may never have grown into a world religion as fast as it did.

Looking back at their origins from a land that barely produced enough to sustain life, and the lasting legacy they eventually left behind, the late scholar J.M. Roberts in his book the Penguin History of the World (see Farbound.Net snippet: The Penguin History of the World), was to reflect:

It was a remarkable achievement for an idea at whose service there had been in the beginning no resources except those of a handful of Semitic tribes. But in spite of its majestic record no Arab state was ever again to provide unity for Islam after the tenth century. Even Arab unity was to remain only a dream, though one still cherished today.

-J.M. Roberts, author History of the World.

The Arabs’, contribution, moreover, was not just restricted to the spread of Islam. In mathematics, philosophy, astronomy, science, medicine and literature, the great thinkers of their land in time were to usher in a new age of enlightenment and advances. Arabian merchants were to teach their European counterparts the art of maintaining accounts. The Arabs’ absorption of the Indian numerical system and its popularity around the known world was to ultimately replace the Roman numerical. The translation of their greatest works into Latin was to gain fame in European lands and inspire western scholars and artists. While their cities of Baghdad, Cairo and Corduba at the beginning of the Crusades were to leave Christian armies awestruck with their wealth and splendour, inspiring architectural revolutions back home. Above all, and among the Arabs’ greatest achievements was the unique cultural identity they eventually endowed on the east by gradually ousting centuries of deep-rooted Hellenic and Roman influences and supplanting it with new and unique eastern forms, which materialized visibly in the arts, architecture and writing during their reign – and set in precedence the trend for later Islamic states to continue the legacy.

Much of what the Arabs’ achieved in their time remains with us today. Ingrained in the core of various disciplines such as the words: zero, tariff, cipher and alchemy that can be found in the English language, and more popularly the witty tales of the Thousand and One Arabian Nights, the fabled Arabian carpets, as well as the colossal masterpieces of brick and stone that blend beautifully into their settings in different parts of the world, adorned with intricately designed motifs and geometrical symbols.

Dear author,

I am very intrigued by the idea that Rub el Hizb could be related to the shrine of the Dome of the rock. I wonder whether it is your own interpretation or something based on research. may I ask what are the evidences or sources?

Hi, this is based on research. The Rub El Hizb and the Najmat Al Quds are similar to each other in many ways. They are both eight-pointed stars for a start. The evidence you seek come from books published by authors on the subject. You can find them in the book section on the site. Some of these are the Art of the Byzantine Era, Middle East Garden Traditions and the Arabs Contribution to Islamic art from the 7th to the 15th Century by Wijdan Ali…

In fact, if you notice the sketch above (of both the Stars and the Dome of the Rock) you will find how aligned the stars are with the building.

Thank you for this article.

Can you please share the author’s name and his references?

This is a Farbound.Net story. It has been researched from the works of historians and authors. Some of these books you can find in the Farbound.Net shopping section. Where possible quotes and source names have been incorporated within the story itself. Some of them are: History of the World. J.M. Roberts, Art of the Byzantine Era, Middle East Garden Traditions and the Arabs Contribution to Islamic art from the 7th to the 15th Century by Wijdan Ali. If you like to discuss further, please feel free to comment here, on the Farbound.Net site or a social site of preference.