Los Alamos Hospital, New Mexico, U.S.A.

Photographer: John Michnovicz.

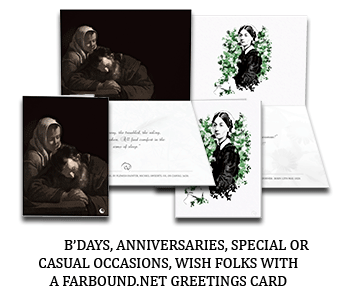

Photographed inside a care unit of the Los Alamos Hospital in Los Alamos, New Mexico. The medical facility of the full-fledged Atomic City that was built to house the scientists, technicians and staff of the Manhattan Project. The terribly burnt and blistered hand in focus is of Harry K. Daghlian. A technician unfortunate to be exposed to a lethal dose of radiation exposure on the 21st of August 1945.

Daghlian at the time was working inside an Omega Site laboratory facility. Some 6,000 miles away from Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Cities, already reeling from the after-effects of radiation exposure. Having been nuked almost two weeks before. He was working for his PhD.

An experienced technician.

Though an intelligent university student, apt at assembling critical components for nuclear experiments with ease and an experienced technician who had been involved in assembling the critical parts of the Trinity Gadget, three months prior, for the test detonation in the Jornada del Muerto desert in July 1945. Harry Daghlian’s fatal mishap is revealed by some scholars to have been the result of his maverick techniques which had been in clear violation of safety procedures.

His accident had occurred during a phase when Manhattan physicists were experimenting with nuclear fission to better understand the sequence and produce improved atomic weapons. This new phase of experiments had begun after it had been discovered that both the ‘Little Boy’ and ‘Fat Man’ in spite of their enormous destructive potential were nonetheless flawed weapons.

In this post-war phase of development, as scientists and technicians had prodded with care in a project known as Tickling the Dragon’s Tail. A project essentially conceived to perfect the sequence of an atomic chain reaction. The 24-year-old Daghlian, confident and closely familiar with this field, had begun to deviate from protocols and experiment with dangerously volatile materials in a highly risky manner. Which surprisingly had alarmed neither his supervisor nor other members of the Critical Assembly group. So much so as to impose corrective measures.

Daghlian’s Project.

The experiment Daghlian had been involved in had required him to build a tungsten carbide enclosure around a plutonium core with 13 pounds tungsten bricks. To warm him of radiation exposure there was a neutron monitor. That had been specifically designed to alert scientists and technicians, like him, of approaching thresholds with a string of sharp clicks. Having conducted the experiment many times to gauge the critical points of a chain reaction, Daghlian was quite proficient with the steps.

On Tuesday, 21st of August 1945, however, as Daghlian after having already worked a twelve-hour shift had returned to the Omega Site laboratory after a dinner break and lecture. He had been eager to try out a new idea and had hastily built a 236 kg tungsten enclosure with only a military guard present a little distance away. He had also paid little attention to the clicks of the neutron monitor which had continuously emitted warnings of critical points.

How the accident happened.

The mishap had occurred at 10:00 p.m. as Daghlian was just about to add the final tungsten brick. Startled to find the neutron monitor rattling furiously he had panicked and attempted to withdraw this last brick with a quick jerk. But it had slipped from his grasp and landed in the centre of the assembly he had built, close to the plutonium orb.

In the tense moments that had followed. Daghlian, without thinking, had thrust his right hand into the enclosure and pulled back the brick. At this point, he had become aware of a tingling sensation and observed a growling blue mist form around his hand. Removing the brick, however, had not helped. As the neutron monitor had still continued to rattle. A thoroughly panicked Daghlian had then attempted to overturn the table. Finding that impossible to accomplish he had then manually removed each and every brick, till the clicking sounds from the monitor had finally abated.

Although Daghlian’s brave effort in controlling the situation had averted a larger catastrophe that evening. He nonetheless had been exposed to 510 rem of radiation from a 6.19 kg plutonium orb inside a 236 kg tungsten reflective enclosure. Which in the end had proved fatal for him – in spite of the medication administered to him, an hour or so later at the Los Alamos Hospital. Measured out in proportion to the radiation absorbed by the coins in his pocket.

The incident had not just stunned the Manhattan community but also opened their eyes to the incurable effects of radiation exposure. Which very likely no one in the team, hitherto, may have anticipated or predicted to have been so extreme.

A photo taken during Daghlian’s hospitilization.

One among a series of photographs that were taken for documentation purposes with the consent of Daghlian himself. This image was created a few days before his death on the 15th of September 1945. By which time Daghilian had been completely bedridden, afflicted by several other ailments other than just his injured hand.

Cared for by his mother and sister. Both trained nurses. Daghilian’s blisters had needed to be repeatedly cut open, cleaned and have the dead skin scraped away. His condition while showing initial signs of recovery had ultimately deteriorated. Medical records indicate, his heartbeat had accelerated to 250 beats per minute.

As the days had progressed, treatment of one ailment had led to the emergence of another. During his last hours, Daghilian had lost all body hair and lived on intravenous fluids. Suffering from internal organ failure, loss of skin, diarrhoea, cramps and fever – with anaesthesia proving to be ineffective against the pain.

After his death on the 15th of September 1945. An initial press statement is reported to have pronounced his death due to chemical burns. Which was later revealed to be from gamma and neuron irradiation.

The first American casualty of radiation exposure.

Widely known as the first American casualty of the Atomic Age. His death, however, was not the only one to come out of those pioneering days of atomic research. Some nine months, his supervisor, Louis Slotin, met with a similar mishap in May 1946. Sloting, exposed to an even higher level of exposure, survived for only nine days (see Farbound.Net story: Risky Experiments).

The military guard on duty on the evening of the 21st of August was unharmed. Having been exposed to only 50 rem of radiation.

Daghlian was a former MIT student. Prior to joining the Manhattan Project in 1944. He had transferred to the University of Purdue in West Lafayette, Indiana, to pursue a doctorate in particle physics. He is today commemorated with a granite monument in his home town of New London in Connecticut, U.S.